On Sunday the Tour of the Gila finished in Pinos Altos, NM, a few miles from Silver City on the continental divide. The Rally pro cycling team was feeling celebratory. They rode downhill back into Silver City for postrace milkshakes at Sonic. It’s a tradition for the winner to treat his team before everybody packs up and heads to airports. Pro cycling teams don’t live or train together and usually only see each other at races.

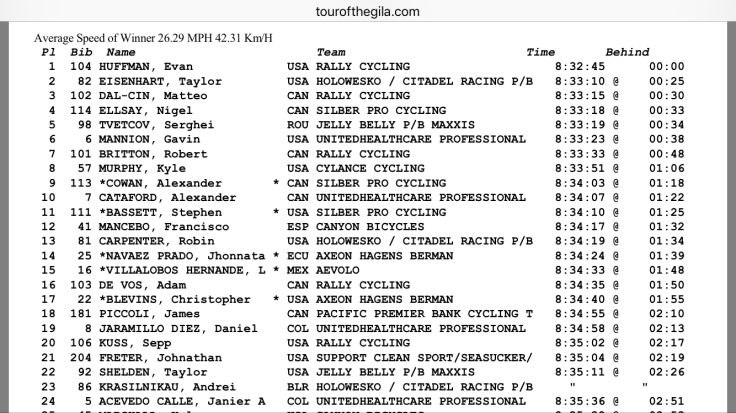

My view of the podium in front of the Buckhorn in Pinos Altos, NM: Team Rally from left: Eric in orange vest, Adam DeVos, Evan Huffman in red race-leader jersey, Rob Britton in polka-dot King of the Mountain jersey, Danny Pate, Sepp Kuss, Colin Joyce, Mateo Dal Cin. Best Overall Team

Inside the Buckhorn Saloon

The terrible thing about the immediate post-race time was that everyone knew that a cyclist from team Axeon Hagens Berman had been badly injured in a crash. He was already evacuated to hospital by helicopter, but there was no news. It’s not unusual for cyclists to crash, and they wear no protective gear except a helmet. Dressing in skintight lycra to avoid wind drag doesn’t help.

Usually there will be a Tweet from hospital with a brave and droll comment from the injured that he has a broken collarbone (the most common cycling injury), or some other shorthand for pain and recovery that other cyclists all understand. No one had anything yet. The Axeon (pronounced “action”) team is a developmental team in the pro ranks, so all the riders are young, generally 23 and under. This rider is 21. Age 21 with no news became two bad things. The third bad thing was that he’d been described as “airlifted with facial injuries,” which meant he’d hit his head. The road where the crash occurred is steeply downhill and he’d been trying to “chase back on,” cycling shorthand for “Oh my God, I’ve got to catch up!” Chasing back to the peloton’s relentless pace in the final stretches of a pro race can be an impossible task, and if you can’t do it quickly chances are you can’t do it at all. My mind at times like this goes to my own son. There’s nothing I can do about that, and it didn’t help that the injured happened to have our same last name. Yeah, so there was that.

We popped down to Silver City ourselves, said good-byes, stopped at an artist store we’d admired, and hit the road. It was still early afternoon, and we had the intent to get into Texas, not so much for love of Texas as to lose the timezone hour. Amarillo would mean eight hours done. First, back to Albaquerqee (still can’t spell it!) by a different route, a beautiful mountain road through Gila National Forest that Tour of the Gila had used as a race route. We hadn’t driven it yet, because we’d arrived last Wednesday by heading straight to the day’s finish line. The road was a gorgeous twisting mountain drive with plenty of S-curve advisory signs down to 15 mph and even 10 mph. Pro cyclists during a race routinely take these at double or even triple the posted limits. A little sand or a small bump can be a problem. We stopped briefly at turnouts, got out of the car, and admired the views. New Mexico: Land of Enchantment. And copper mining. And road runners and lizards and tumbleweed.

Armadillos too? No, those were the next day. In Missouri we had a contest going to see who could spot roadkill armadillos first. We saw a combined fifteen dead armadillos! Sure there were the occasional raccoon or possum as well, but those armadillos! Armored, but not enough to cross a highway.

**Note: one correction, I found out later that Chad Young whom I described as trying to “chase back on” was, in fact, bridging up to the lead group in the race– same effect on the frantic nature of the effort required, but a world of difference in what it means to cyclists. I regret that error

The flowers. Yeah, not sure why, but bicycle racers get flowers when they win.

The flowers. Yeah, not sure why, but bicycle racers get flowers when they win.